This might sound strange, but I love it when my little readers make mistakes. And it’s definitely not because I want to see them fail!

Rather, seeing those mistakes gives me incredible information about what my students can do, as well as what they’re not yet doing. It helps me figure out what decoding strategies to teach, what phonics patterns they need to work on, and what kind of coaching I can use to best support them.

In today’s post, I’m going to share exactly how I use running records to analyze students’ decoding errors in order to gain information about them as readers. I also have some freebies that will help you better understand exactly what your students need!

(Note: this post is part of a 6-post series on reading interventions! If you missed the first post in the series, you can check it out here.

There are many different literacy assessments out there that can give us data about our students’ reading. And although it’s one of the simplest assessments out there, the running record is one of my favorites.

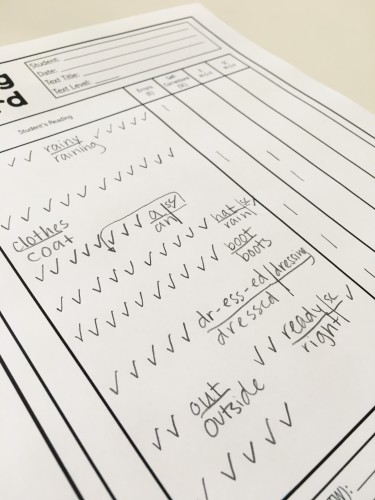

When you take a running record, you not only record when students make mistakes, but you also write down their miscues (the word(s) they say instead of the correct word) and self-corrections (when they fix up their mistakes). Students’ miscues and self-corrections give you information about what they are doing while they read, as well as what they are not yet doing. Knowing this is incredibly valuable because it helps you figure out what to teach your kiddos next!

Here’s an example:

A student is reading the sentence, “We looked at the bridge” on a page where the photo shows two children looking at a bridge.

If the child reads, “We looked at the book” and does not correct the error, this tells me a couple of things. First, the child uses the first letter of a word when attempting to decode an unfamiliar word. Second, the child is paying attention to sentence structure (the sentence still sounds right despite the mistake).

However, the child is not reading all the way through the word, and the child is not consistently attending to meaning (she should have realized that “bridge” doesn’t make sense).

That one tiny mistake gives us a lot of potential information about that reader. If the reader continues to make similar errors throughout the rest of the book, this provides further support for our inferences about what the reader is and is not doing.

So how do you prepare for a running record? Well, the nice thing is that getting ready is pretty simple.

First, choose a text that will be at the student’s instructional level. Read the book (if you haven’t already), grab a blank running record form, and prepare a couple of comprehension prompts.

If you need free running record forms, sign up to receive them by clicking HERE – but be sure to read the rest of this post so you’ll know how to use them!

Then, carve out time to give the running record to the student. Since it’s a one-on-one assessment, this can get tricky. I like to build running records into my small group time, so that I’m doing them on a consistent basis.

When my students sit down at the table to begin a small group lesson, they reread familiar texts from the group’s book box. Meanwhile, I grab the book that we read during the previous lesson and have one student read it to me. I take a running record of the child’s reading and ask a few comprehension questions afterward.

As a classroom teacher, I took one running record per group per day. This way, I got through my entire class about once a month. I do take running records on some students more frequently, because their group is “lower” and is meeting with me more often than the other groups. This is a good thing, because it allows me to keep a close eye on my struggling readers’ progress.

When you take a running record, you have to move fast! The more you can write down about a child’s miscues and reading behaviors, the better. If you’re just starting out with running records, you may find it tricky to keep up with a child’s reading. The more you practice, the easier it’ll be (although I still don’t catch everything if a child is reading quickly).

Sometimes, you’ll have a running record that contains the words of the text. Reading A to Z has some books that come with running records, as does the Fountas and Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System.

However, you can just as easily take a running record on a blank form or even a blank sheet of paper if you’re in a pinch! Let’s take a look at how you would take a running record using a blank form.

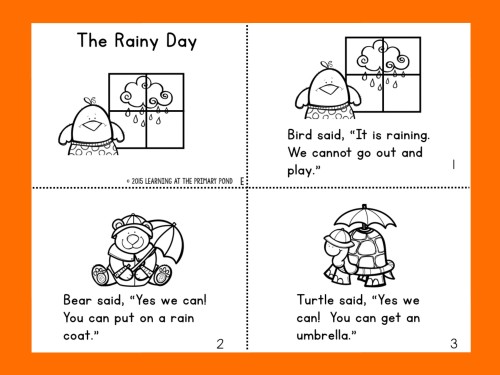

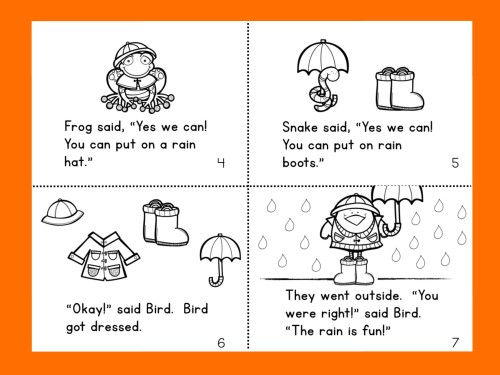

First, let’s imagine that a student is reading this text. Here is a layout of the complete text:

Watch this video to see how I take a basic running record (I don’t actually have a student with me during the video, so you’ll have to use your imagination!). You can follow along with the actual text using the images above.

There are different ways to mark down reading behaviors and errors. Always stick with the system agreed upon by your team or school, for purposes of consistency.

You can take a look at the Reading A to Z running record scoring suggestions, as well as Heinemann’s version. If your team or school doesn’t have an agreed-upon system, perhaps you can initiate that conversation. Consistency in this area can be helpful when a team is examining student assessment data.

Once you’ve taken the running record, take a few minutes to look it over. Although I don’t always have time to look over my running records the same day that I take them, I always sit down with a pile of them at least once a week. I use the information I gather in order to plan next week’s instruction.

First, count up the number of errors. Take the number of words read correctly (WC), divide that by the total number of words in the book (TW), and then multiply that number by 100 (WC / TW x 100). That will give you the percent of total words read accurately.

In the running record in the video, the “reader” made 5 errors (we don’t count the ones he self-corrected). There were 74 total words (TW), so he read 69 of them correctly (WC).

69 / 74 x 100 = 93. The child read this book with 93% accuracy.

The percent of words read correctly gives us some information about whether this book and the child were a good match. When a beginning reader can read a text with 95% accuracy or higher, that book is at the child’s independent level. She can read it without support, on her own.

When a beginning reader reads a text with 90%-94% accuracy, we consider the text to be at her instructional level. The imaginary child in my running record read this text with 93% accuracy, indicating that this text is probably at his instructional level.

Reading a text with lower than 90% accuracy generally means that the text is too difficult for the reader.

By itself, however, the accuracy percentage doesn’t tell the whole story.

We also have to take a look at comprehension and fluency. I’m not going to dive deep into either of these areas, because decoding is the focus of this blog post series. However, it’s important to look at comprehension when considering instructional level. Even if a child reads a text with a high level of accuracy, it’s not at his instructional level if his comprehension of the text is poor. We shouldn’t choose books for our students that they cannot comprehend at all, because even supportive teaching will not be enough to help the child “bridge the gap” and understand the text.

It’s also important to consider fluency when determining an instructional level. A child may read a book with good accuracy and comprehension – but if it takes the student half an hour to finish the book, then it’s not a good choice for guided reading time! To quickly rate a child’s fluency on a running record, I like to jot down a number between 1 and 3 (1 = disfluent, 2 = somewhat fluent, and 3 = fluent). It’s very simple, and I can elaborate with notes, but it’s a quick and easy way to address fluency on a running record.

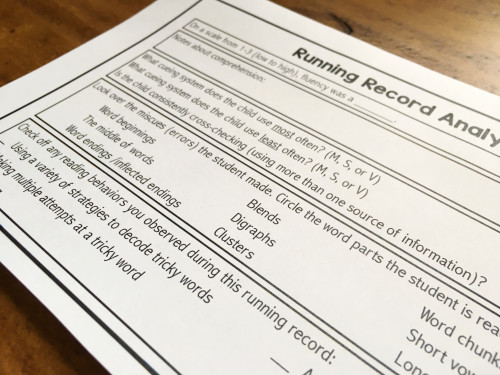

In the free intervention toolkit, I’ve included several different running record forms to help you calculate reading accuracy, rate comprehension, and score fluency. Again, you can sign up to receive those intervention materials here:

But wait…there’s more!! Even after I’ve scored the running record for accuracy, I’m not done looking at it. Now it’s time to use all this information to draw conclusions about the reader.

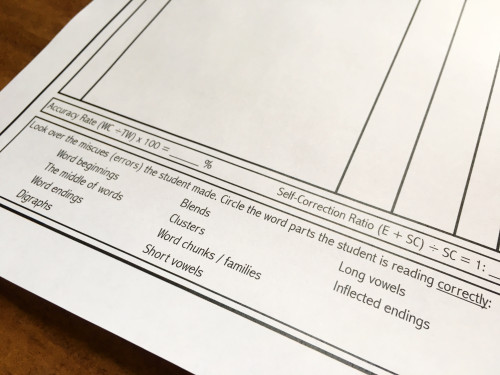

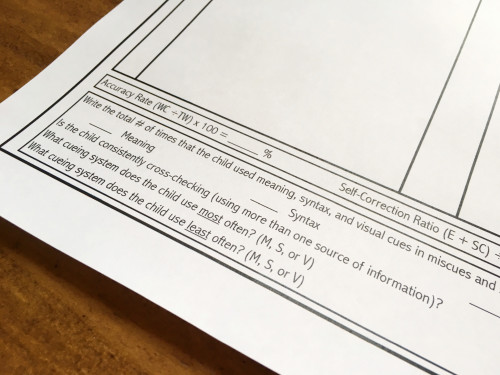

By looking at the words that a child misread, I can figure out what phonics patterns he/she needs to work on. Here is a list of some of the things I look for with beginning readers (this list is also included in the free intervention toolkit that you can sign up for above):

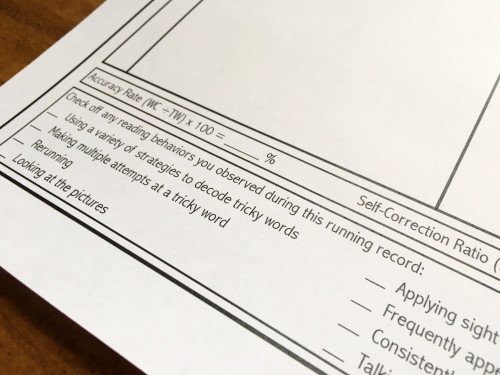

In addition to considering a child’s word reading habits, I also look for information about his general reading behaviors. I search to find out if the child is:

I also look at fluency (attention to punctuation, smooth reading, expression, etc.), but I won’t go into that here since our focus is decoding.

When you download the free intervention toolkit (sign up below the photos), you will find several different types of running record forms. These “at a glance” forms will help you quickly find and summarize information about students’ error patterns and reading behaviors!

Running records can truly serve as a gold mine for information about students’ reading. However, all the data we get is only valuable when we use it to take action!

To continue exploring how to support your students (especially your struggling readers) with decoding, check out the rest of the blog posts in this (now finished) series:

Pinnell, G. S., & Fountas, I. C. (2009). When readers struggle: Teaching that works. Heinemann.