Plastic makes our society more practical and safer. It is hard to consider eliminating plastic in some sectors, such as the medical field. However, after use, plastic waste becomes a global problem without precedents, and when not properly disposed of, it can cause several socio-environmental problems. Some possible solutions are recycling, the circular economy, proper waste management, and consumer awareness. Consumers play a crucial role in preventing problems caused by plastic. In this work, consumer awareness of plastic is discussed according to the point of view of the research areas—environmental science, engineering, and materials science—based on the analysis of the main authors’ keywords obtained in a literature search in the Scopus database. Bibliometrix analyzed the Scopus search results. The results showed that each area presents different concerns and priorities. The current scenario, including the main hotspots, trends, emerging topics, and deficiencies, was obtained. On the contrary, the concerns from the literature and those of the daily lives of consumers do not seem to fit in, which creates a gap. By reducing this gap, the distance between consumers awareness and their behavior will be smaller.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The correct management of plastic waste is a complex and delicate task. Several characters are involved but the consumer has a relevant role, being responsible for segregating and discarding all the waste they produce.

The greater the economic prosperity of a region is, the greater its municipal solid waste (MSW) composition complexity [1]. More available products and services for citizens occur as countries and cities become more prosperous and more populated [2]. In high-income countries and cities, packing wastes, especially plastics, are predominant among all the waste produced [3]. Consequently, the higher the MSW composition complexity, the greater the difficulty of managing it, especially the correct management of plastic. Plastic is ubiquitous in our lives and modern society, being a massive increase in the production of fibers and resins, from 2 Mt in 1950 to around 380 Mt in 2015 [4].

Plastic plays a unique socioeconomic role. Worldwide, thousands of jobs are generated, whether in the production or recycling of plastic [5]. Thus, in addition to contributing to the economy, it plays a tremendous social role. Employment can be defined as a source of income and also a link of its identity over individual attributions introduced by its achievement of the task [6]. In addition, employment means social integration, allowing contact among people, insertion, and the feeling of belonging to a group [7].

However, even with a tremendously positive influence on society [5], plastic pollution outperforms it, making plastic a major polluter. Over the years, people have accompanied a significant increase in the pollution of water bodies by plastic, reaching up to 53 Mt per year by 2030 [8]. According to Geyer et al. [4], around 6300 Mt of plastic waste had been generated up to 2015, being recycled only about 9% of this amount.

Even with legal procedures, regulations, and levies regarding the reduction of single-use plastic [9,10,11,12,13,14], knowing that the circular economy is crucial to reduce plastic pollution [15, 16], and knowing all the problems that plastic can cause when improperly disposed of, some consumers do not fulfill their role regarding the correct segregation and the final disposal of plastic waste that they produce. Some authors consider consumers as a primary source of plastic pollution [17] due to their lack of awareness or contribution to dealing with plastic. Besides, consumers may not want to put information into practice on individual actions relative to environmental and economic benefits [17].

Bibliometric analysis is an important instrument used to have an overview of different knowledge areas. Using specific software programs, the data of the publications collected from a search in a given database can be analyzed from a quantitative point of view. Among the possible data to be analyzed, the investigation of the keywords is essential to determine the research trend, identify gaps in the discussion concerning a given subject/research area, and identify the fields that can be interesting as future research areas [18]. The obtained results are relevant to influence new researchers to achieve progress in a given research area.

Considering the distinct role of consumers in the correct management of plastic waste and all the consequences that its incorrect management is likely to result in, consumer awareness of plastic was discussed, according to the literature of the last two decades. The analysis was based on the analysis of the main authors’ keywords obtained from a search in the Scopus database. Deepening the discussion, the point of view of the research areas—environmental science, engineering, and materials science—was also studied. The primary purpose was to comprehend the contribution of each area in developing consumer awareness of plastic. The results have shown that each area has different concerns and priorities. The current scenario was obtained by including the main hotspots, trends, emerging topics, and deficiencies.

Awareness is the knowledge that something exists or the understanding of a situation or subject based on information or experience [19]. Thus, within the scope of this work, although consumers know the problems that the incorrect disposal of plastic waste causes and the possible actions to mitigate existing problems, they do not collaborate positively.

Thomas [20] categorized four dynamic and ever-changing forms of non-recognition or unawareness, trying to elucidate why pollution is ignored:

In the circular economy, waste is a raw material. Waste is a resource continually circulated within the economy [21]. It is a valuable material. The consumer is responsible for making available correctly the recyclable waste they produce for selective collection. The consumer is responsible for reintroducing the plastic waste to the cycle again (Fig. 1 item 3). Then, the plastic waste is collected, separated, and washed, i. e., it is prepared for recycling (Fig. 1 item 4). Plastic is recycled (Fig. 1 item 5), becoming a raw material for producing new items. In the sequence, it is transformed into other items (Fig. 1 item 1). After, the items made of recycled plastic go to consumer markets (Fig. 1 item 2), and then, consumed again (Fig. 1 item 3), closing the cycle (considering the mechanical recycling). This cycle constitutes the circular economy (Fig. 1). However, the role of the consumer regarding plastic does not end at that point—it goes far beyond. Some authors [22] have identified 14 critical roles of the consumers in reducing plastic pollutants, as follows:

The lack of consumer awareness plays a crucial role in recycling rates. In some countries, such as Brazil, recycling rates are meager—only about 4%. Even worse, it causes plastic pollution, mainly in water bodies (as aforementioned), which causes negative impacts on the environment, fauna, and human health.

Plastic is found in several sizes in different water bodies around the globe, but the most common are microplastics [24,25,26,27,28,29], fragments of polymeric origin with dimensions between 1 and 1000 μm [30]. Some products, such as wet wipes [27], sanitary towels [27], and face masks [31,32,33], are sources of microplastics in water bodies when improperly disposed of.

Microplastics in water bodies damage different organisms as they cannot distinguish them from food [34]. The accumulation of plastic in their organisms hinders digestion and the absorption of nutrients, reducing the reserve of energy available and leading to premature death [35]. As a shocking example, news addressed a Magellanic Penguin found dead on a beach in the city of São Sebastião, on the north coast of São Paulo (Brazil). During its necropsy, a face mask (made of plastic) was found in its stomach (photo in the center of Fig. 1), the cause of its death [36].

Microplastics can be easily ingested by aquatic animals and by humans due to their small size. Additionally, microplastics can adsorb different contaminants, increasing their toxicity. It is estimated that humans ingest up to 5 g of microplastics per week [37]. The literature points to inflammation as the major impact of microplastics on human health [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. Recently, microplastics were detected in breast milk for the first time [52].

The methodology used in this work is described by de Sousa [53]. The bibliographic data inputs were obtained through a Scopus search on 12 August 2021. The keywords used were (consumer*) AND (awareness OR consciousness) AND (plastic* OR polymer*). Reviews and articles in English were considered from 2001 to 2020.

From Scopus, a scopus.bib file containing the data was taken, and a bibliometric analysis using the Bibliometrix (an R-package) was performed.

Next, from the Scopus search, the results obtained were limited to environmental science, engineering, and materials science research areas. For each area investigated, a scopus.bib file with the data was recorded and used to analyze the authors’ keywords.

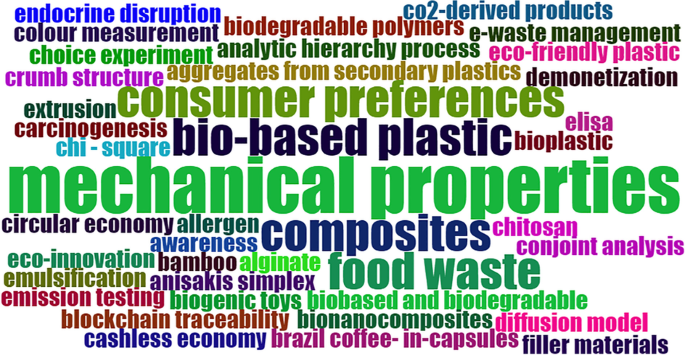

The word cloud contains the 50 most frequent authors’ keywords. Five keywords per year with a minimum frequency of occurrence of 3 were analyzed for the evolution of the main terms.

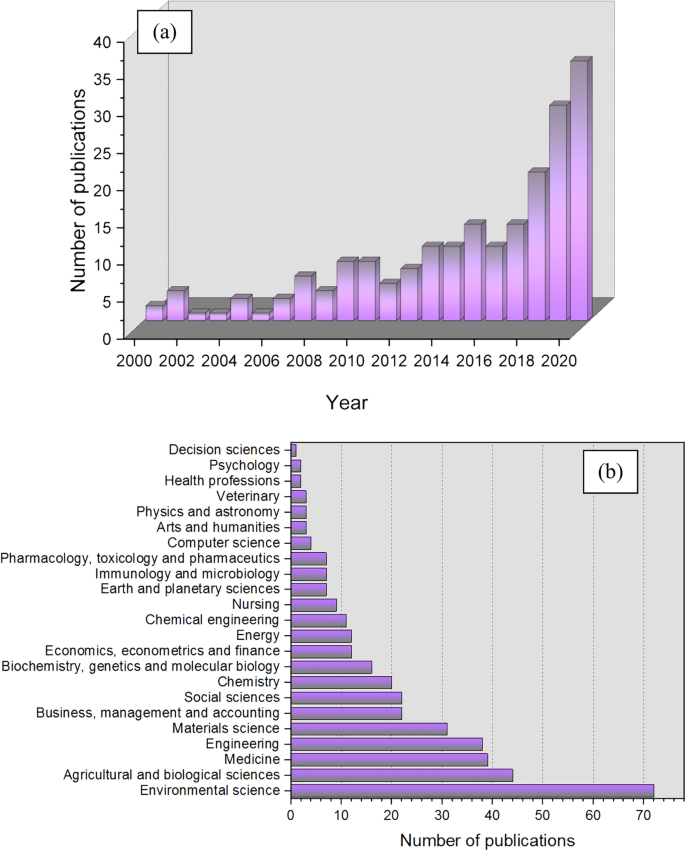

The Scopus search obtained a total of 191 publications, with 156 articles and 35 reviews in English. The number of publications per year and area is presented in Fig. 2.

The results show a growth in the number of publications over the period, with an annual growth rate of 15.39% (according to Bibliometrix). Even with a trend of increase in this figure, the number of annual publications is still low given the great relevance of the subject, and also demonstrates a real possibility of growth and improvement in the area, with ample space for research and development [54].

By analyzing the authors’ keywords, it is possible to obtain a panorama of the research field [55], as well as the hotspots and future trends. Authors use keywords to communicate their wishes to readers and the scientific community [56]. Some authors [54] explain that “keywords are the core of the paper, which indicates the research direction of the field by abstracting and summarizing the research content of the academic paper.” Given the importance of analyzing the authors’ keywords, they will be discussed in the present work.

The research area of consumer awareness of plastic (encompassing all the involved research areas) will be analyzed in the sequence.

From the 191 publications, a total of 720 authors’ keywords were obtained. The most relevant are as follows (number of occurrences in parenthesis): waste management (9), recycling (8), sustainability (7), plastic waste (6), packaging (5), consumer behavior (4), microplastics (4), pollution (4), and biopolymers (3). These keywords are hotspots concerning consumer awareness of plastic, especially waste management [57, 58].

Figure 3 presents the word cloud containing the 50 more frequently observed authors’ keywords in the results of the Scopus search about consumer awareness of plastic and the trending topic. The word cloud analysis can provide an overview of the current literature about consumer awareness of plastic. The size of the letters represents the frequency of the keyword. The word cloud contains the authors’ keywords that are more relevant in the field. Therefore, as a panorama is provided, the discussion can be deepened.

Based on the authors’ keywords with the highest frequency and the word cloud, a concern from the literature about the problems that plastic (“plastic waste,” “packaging”) can cause/aggravate in the environment can be observed (“pollution,” “microplastics”), as well as the possible solutions to mitigate them (“consumer behavior,” “waste management,” “recycling,” and use of “biopolymers” and “biodegradable polymers”). This result also demonstrates the vital role of consumers in the plastics recycling chain through their pro-environmental behavior (“consumer behavior”).

Some possibilities to mitigate plastic pollution include the correct “management of plastic,” “recycling,” “levies,” and “consumer behavior.”

Other concerns depicted in the word cloud are the management of “e-waste” [59] and “food safety” [24, 58].

Single-use plastic is a massive concern in consumer awareness of plastic research. Around 49% of the global production of plastic is constituted by single-use items [60]. The point to be considered is that single-use plastic has a very short lifetime, being discarded just after use and consequently becoming responsible for enhancing the environmental damages and concerns caused by plastic waste. According to Forbes [61], around 160,000 plastic bags are used per second worldwide, and only less than 3% of this amount is effectively recycled. The literature [62] describes a more negative perception towards single-use plastic and relatively high awareness of the environmental impacts they cause, as observed in the word cloud due to the keywords “plastic straws” and “plastic bags.” Negative discernments of single-use plastic consumption are linked to higher levels of environmental awareness [63, 64]. On the other hand, even knowing the negative impact of plastic, some consumers still use them indistinctly [65].

According to Winton et al. [64], the most found macroplastics in freshwater environments in Europe are single-use short-term food acquisitions. Single-use plastics contribute to 60–95% of global marine plastic pollution [9]. So, abolishing all single-use products can effectively protect the environment and the world’s oceans [63].

Consumers can decide to reduce single-use plastic bags (SUPBs) in their daily life and engage in pro-environmental behavior [63]. In Chile, an informal and uncoordinated alliance of different sectors, including science, media, the general public, government agencies, schools, and universities, promoted the demise of SUPBs [63].

The literature points out to the circular economy and recycling as possible solutions for plastic waste management. The commitment of consumers, government, and companies (through the extended producer responsibility [66]), as part of the circular economy, is essential for reducing/solving the massive problem of plastic management since each sector is co-responsible for the environmental problems generated by plastic [55].

According to Fig. 3b, the evolution of the main terms can be visualized. Some terms have been kept in evidence in the literature for an extended period, such as “mechanical properties,” “consumer behavior,” and “food safety.” However, they have lost their evidence to other terms, such as “packaging,” “sustainability,” “marine debris,” “microplastics,” and “plastic waste.” The terms with the highest frequency are the most popular authors’ keywords, as depicted before. The term “waste management” has been kept in evidence from 2012 to 2020. It has the highest frequency, corroborating Fig. 3a. The terms with the highest frequencies, as mentioned previously, are currently in evidence, being considered hotspots in the research field of consumer awareness of plastic.

Regarding the authors’ keywords, 584 are from articles, and 136 are from reviews.

Based on the analysis of the authors’ keywords, emerging topics and trends are obtained. Trends or, in other words, subjects highly investigated, are present in reviews, whereas emerging topics are present in articles [67].

Table 1 presents the most frequent authors’ keywords in articles and reviews. The minimum number of occurrences for each keyword is 2. The keywords were separated into the following categories: actor, source, problem, mitigation, consequence, and policy. The main problem was plastic pollution (“microplastics,” “marine debris,” etc.). The actor is responsible for the problem, i.e., “consumer behavior.” The sources are the ones that produce plastic pollution, such as “plastic waste.” The consequences are the effects of plastic pollution. Mitigations lessen the consequences of plastic pollution. Furthermore, a policy is a rule to be followed by the population, such as a ban on a given plastic item. Plastic packages act as a barrier, protecting food against damage (food safety), and reducing food waste. However, some additives in the plastic can migrate to food in contact with the package, resulting in health impacts. So, the authors’ keywords “food safety,” “food contact material,” and “food waste” were categorized into a consequence.

The role of consumers is evidenced through the keywords “awareness of consequences” [72], “consumer preferences” [73, 74], “attitude,” “theory of planned behavior” [75], “beliefs,” “behavior-based solutions,” “behavior change” [76], “anti-consumption behavior” [77], “awareness” [68, 78], “choice experiment” [74], “behavior,” “consumer behavior” [62, 64], “pro-environmental behavior,” and “willingness to pay” [79]. Some keywords present a minor frequency. The high number of keywords concerning the behavior of consumers shows that the environmental science area focuses on consumers. Their behavior and consumption are responsible for environmental problems caused/aggravated by plastic. As aforementioned, consumers also play an essential role in correctly managing plastic and its recycling [75] (Fig. 1).

Other possible solutions to mitigate the problems that plastic can cause are posed by the environmental science area, such as the use of “bioplastic bottles,” “bio-based packaging” [80], “biodegradable plastic bottles” (in substitution for conventional plastic bottles [81]), “bio-based plastic,” the correct “management of plastic waste” [63], “recycling” [75], and “plastic bag levies” [77, 79, 82].

Habits, norms, and situational factors predict the behavior of consumers. Despite a pronounced awareness of the associated problems that plastic can cause, consumers keep on appreciating and using it [65]. In Taiwan, some authors [1] demonstrated that the plastic and glass waste generation rate declined when economic activities expanded, mainly due to the strict enforcement of recycling policies accompanied by marketing campaigns encouraging recycling and enhancing the green awareness of consumers. Accordingly, an opportunity to increase consumer awareness is to encourage the opening of zero-packaging grocery stores, improving the social and environmental impacts of the food supply chain [78]. Another example of the importance of consumer behavior is the ban on SUPBs in Chile [63], which was driven by a broad concern among the general public, and led to a bottom-up movement culminating in the national government taking stakes in the issue.

Literature also analyzed the consumer perceptions of microplastics in “personal care products” [83], of using “compostable carrier bags” [84], and “plastic water bottles” [81]. Orset et al. [81] analyzed the perception and behavior of consumers of plastic water bottles, which depend on the viewpoint (i.e., consumer, producer, and social welfare). From the consumer point of view, the authors recommended the organic policy with subsidy, the three tools of the recycling policy, and the biodegradable policy with subsidy. Concerning the compostable carrier bags [84], a greater awareness was observed regarding the use of these bags and the recognition of the importance of green products, which are gaining space in the market and in the routine of consumers. Furthermore, about microplastics in personal care products [83], participants of the survey perceived the use of microbeads in such products as unnatural and unnecessary.

From the Scopus search about consumer awareness of plastic limited to the engineering area, a total of 131 authors’ keywords were obtained in the 33 publications (24 articles and 9 reviews). The most frequently used keywords by the authors of the engineering area are as follow (frequency of occurrence in parenthesis): mechanical properties (3), bio-based plastic (2), composites (2), consumer preferences (2), and food waste (2). All the other keywords present the same frequency.

The word cloud containing the 50 more frequently found authors’ keywords in the results of the Scopus search of the engineering area is shown in Fig. 5.

Based on the analysis of the authors’ keywords, the engineering area demonstrates some options to mitigate the impacts that plastic pollution can cause; options such as the “circular economy,” “e-waste management,” the use of “biodegradable polymers” [85], “bio-based plastic” [73], “composites” [86], “chitosan” [87], “eco-friendly plastic,” “bioplastic,” “bamboo” [88], “alginate” [87], “biobased” and “biodegradable” [89,90,91], “bio nanocomposites” [92], “CO2-derived products” [93], and “filler” materials. All these materials are possible options for producing materials that are more environmentally friendly.

As an example of using biobased/biodegradable polymer, some authors [91] studied the feasibility of biobased/biodegradable films for in-package thermal pasteurization made of polylactic acid (PLA) and polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PBAT). The results indicated that selected PLA and PBAT-based films are suitable for in-package pasteurization and can replace polyethylene for ≤ 10 days of shelf life at 4 °C.

This area focuses on economic aspects to encourage the use of materials that cause less environmental impacts, such as “demonetization” and a “cashless economy” since financial encouragement is considered an effective way to reduce plastic debris [76]. “Credible alternative actions and products offered by businesses or through legislation at competitive costs can produce positive behavior changes that eventually reduce plastic pollution” [17].

The area also alerts people to a material that causes a substantial environmental impact, the ‘Brazil coffee-in-capsules’ [94]. According to the authors [94], coffee consumers have a dominant role in helping turn coffee capsule waste into a financial resource or supporting other efforts toward circular practice, emphasizing the behavior and awareness of consumers.

This attitude also raises an alert of possible problems to human health caused/aggravated by the use of plastics with the presence of the keywords “endocrine disruption,” “carcinogenesis,” “allergen,” and “biogenic toys” [74] (to avoid “children contamination” [95]). These keywords express some consumer concerns about the use of plastics.

Even knowing that packages act as a kind of barrier protecting food against damage, extending the lifetime of foods [5, 33], and reducing food waste [78, 96] (another keyword present in the word cloud), additives contained in plastic can migrate from packaging to the food due to diffusion processes (keyword “food contact material,” also shown in the word cloud). As an example of the diffusion process, the release of bisphenol A (BPA), a monomer used in the manufacture of epoxy resins, from polycarbonate products such as plastic baby bottles, baby bottle liners, and reusable drinking bottles is proven by literature [97,98,99]. BPA (endocrine-disrupting chemical) is toxic and can cause several health problems, from cancer to the development of problems in the formation of sexual organs of babies and children, depending on the contamination level [98]. Additionally, additives can contaminate soil, air, water, and food [100, 101].

The research area also demonstrates the critical role of consumers regarding plastic use and its environmental impact through the keywords “consumer preferences” and “awareness” [78, 102].

From the Scopus search about consumer awareness of plastic limited to materials science, 72 authors’ keywords were obtained in the 28 publications (20 articles and 8 reviews). The most frequently used keywords by the authors of the materials science area are as follow (frequency of occurrence in parenthesis): recycling (3), antibacterial (2), and mechanical properties (2). All the other keywords presented the same frequency. The smallest frequency of the keywords of the engineering and materials science compared to the environmental science area is due to the smaller number of publications and authors’ keywords.

The word cloud containing the 50 more frequently found authors’ keywords in the results of the Scopus search of the materials science area is shown in Fig. 6.

The keywords of the materials science area seem to show more significant concerns about the materials that compose the plastic, such as “high-density polyethylene” (HDPE) [103], “aliphatic polyesters” [90], “PET” (polyethylene terephthalate) [104, 105], “additives” [106], “antioxidants,” “kenaf fiber” [107], “antifogs” [106], “bamboo” [88], “dyes/pigments” [108], “bamboo rayon” [109], “copper nanoparticles,” and “biodegradable polymers” [89, 90]. Some of these keywords express the search for more environmentally friendly materials (for instance, the use of “natural fibers” [110] and “biodegradable polymers” [89, 90]), aiming at reducing environmental impacts caused by plastic.

Concerning materials, a meaningful example is the one by Stoll et al. [108], which analyzed the use of carotenoid extracts as natural colorants in PLA films. According to the authors, using carotenoids as colorants for polymeric materials represents an environmentally friendly way of obtaining colored packaging. Beyond the environmental advantages, this natural colorant reduced the oxygen permeability and presented a lubricant effect, increasing the film elasticity up to 50%. Some authors [110] investigated the processing of natural fibers in an internal mixer to be used for thermoplastic lightweight materials, which means a good alternative for the automotive industry.

The primary possibility to solve the problem of plastic waste posed by the area is “recycling” and others, such as the use of plastic residues in the production of “lightweight concrete” [111], “construction materials,” “composites,” and in “3D printing” [104]. 3D printing is an option for the recycling process of post-used plastics, as in the example of using PET [104].

Biodegradable polymers can be considered an option to reduce solid waste disposal problems and reduce the dependence on petroleum-based plastics for packaging materials [90]. However, some authors [89] detected some problems, namely, cost control, in-depth development of functions and applications, materials source extension, enhancement of environmental protection awareness and regulations, and systematical assessment of environmental compatibility of the biodegradable polymers.

All these possibilities should present the necessary mechanical properties for their specific final applications, demonstrated by the keywords “mechanical properties,” “compliance,” and “durability.” Also, the keywords “finite element analysis,” “kinetics,” “computational fluid dynamics” [112], and “package design” indicate some possibilities for analyzing the properties of a given material and design. Computational fluid dynamics (the “finite volume method”) was used to analyze the airflow and the heat transfer performances in the design and performance evaluation of fresh fruit ventilated distribution packaging by Mukama et al. [112], being that the vent-hole design affects cooling and strength requirements.

Some health impacts of plastic and some benefits are also presented, such as “heavy metal testing” [105], “antimicrobial” [113, 114], “antibacterial” [109], “exposure” [115], and “antimicrobial fruit quality.” The research area does not demonstrate the role of consumers in the problems that plastic can cause. However, it presents some possibilities for consumers to act actively and consciously through the presence of keywords “chemical education research” [116], “evaluation strategies,” and “environmental protection.”

Concerning the use of recycled polymers, some authors [117] analyzed the removal of the odor from HDPE by using a modified recycling process. Removing this type of contamination is considered a challenge in the industry and vital to establishing viable concepts for a circular economy for post-consumer HDPE packaging.

Based on the analysis of the authors’ keywords, the materials science area is more focused on solving environmental problems caused by plastic through designing and producing materials that cause a lower environmental impact and are more environmentally friendly options. It is also a way to make consumers more aware of their role when using plastics, providing consumers with options that cause less environmental impact.

The work of Rhein and Schmid [68], which verified the real concerns of consumers regarding plastic packaging from a quantitative analysis based on consumers interviews, showed that consumer awareness involves the following five different aspects:

According to the authors [68], “the different types of awareness strongly reflect how consumers think about problems associated with plastic and whether they feel that they are responsible and, therefore, able to change the current situation.”

As stated before, consumers may not want to put information into practice on individual actions relative to environmental and economic benefits [17]. In other words, many consumers have the information they need to dispose of plastic waste correctly and would rather avoid cooperating. So, consumers have a crucial role in the correct segregation and final disposal of plastic waste, but, unfortunately, some do not fulfill their role (Fig. 1), and consequently, several socio-environmental problems caused by plastic are aggravated. An example that can be observed daily is the significant increase in the number of face masks improperly disposed of on the streets during the COVID-19 pandemic. They end up going into water bodies and can kill animals (Fig. 1). These masks are degraded and release plastic microparticles [23, 33, 118].

Behavior changes can be blocked by psychological and practical barriers, turning the awareness raising into tortuous action [119]. Plastic-related behavioral change is not very successful if the focus is only on information and raising awareness [65]. Stakeholders interviewed by Steinhorst and Beyerl [120] agreed that consumers are not the most responsible agents of change but rather partners of producers, retailers, politicians, and disposal agencies, in which producers and retailers are considered the main agents. Private and public sector initiatives, well-enforced policies, and evidence-based media reporting can provide new norms and practices that are socially accepted [17]. According to Parashar and Hait [69], the primary drivers of plastic misconduct are the lack of awareness and attitude of consumers and their irresponsible behavior, as well as the stress on waste management infrastructure in terms of collection, operation, and financial constraints.

The impact of COVID-19 on people’s consumption behavior worldwide was studied [121], having the following as main results:

These results reveal the increase in the production of recyclable materials in homes and the lack of environmental awareness of most of the respondents. Contradictorily, just 32% segregated the waste they produced but demonstrated concern about the new design of packaging containing less plastic.

Likewise, Rhein and Schmid [68] demonstrated a similar profile of consumers and their awareness of the use of plastic. At the same time, some consumers are willing to pay more for other options that cause less pollution, citing concern for families and especially grandchildren. They claim that plastic pollution is the fault of Africa, Asia, and the Americas (i.e., outside Europe, where the research was performed). They know that the amount of plastic used in packages is large and sometimes unnecessary, such as plastic in shell fruits. However, these consumers cannot help change and assign responsibility to companies. A particular sort of laziness and a wish to buy goods without restrictions override the consciousness that the existing plastic system would, in principle, be changed. Some consumers are conscious of the use of plastic and know the problems they cause to the environment but agree that plastic is practical, unwilling to alter their consumption behavior. That is, “others” are responsible for pollution, not “me.”

Considering consumers’ daily consumption, hygiene, food safety, and practicality of use are more important than the environmental impact [122]. In the review of Heidbreder et al. [65], in which 187 studies were analyzed, people appreciate and regularly use plastic despite a noticeable awareness of related problems. Also, Nguyen [123] analyzed factors that affect Vietnamese consumers’ intention and behavior to bring their shopping bags (BYOB). The results illustrated a modest relationship between intent and authentic behavior concerning BYOB.

So, the literature shows a gap between consumer awareness and behavior. The literature needs to be focused on reducing this gap. According to Ali et al. [22], there is a lack of literature about the explicit roles of consumers, corroborating with the present work. The interrelationships among the consumer’s roles were identified by the authors, which provided action plans for decreasing plastic pollution.

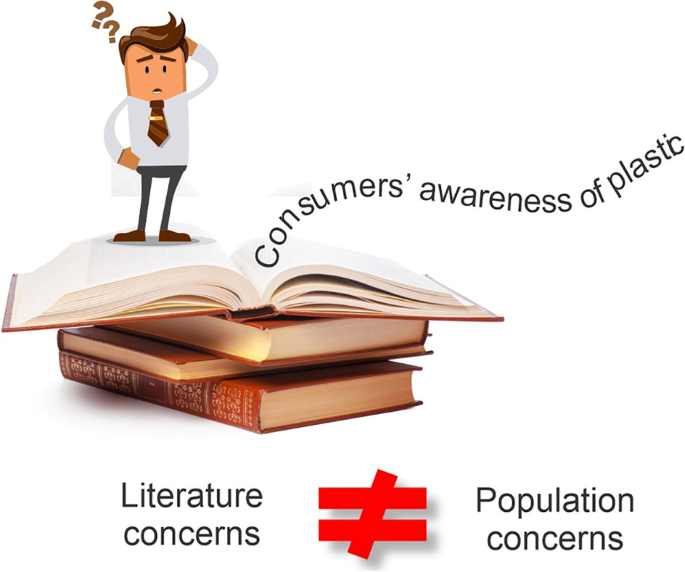

According to the obtained results, each knowledge area has its concerns and priorities regarding consumer awareness of plastic. Nevertheless, such concerns and priorities are not in line with the ones of consumers in everyday life. Thus, by reducing this gap, literature can be a strong partner, for example, in the decision-making of authorities, such as in the creation of laws and norms aimed at reducing the real problem of the final disposal of plastic waste. “Consumers-citizens can greatly contribute to solving the plastic pollution problem and can be used as a stepping stone for further interdisciplinary research” [17].

As an example of the magnitude of the literature, Wang et al. [124] systematically reviewed and compared the publications related to plastic pollution before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the main results, the authors observed that the total number of publications during the COVID-19 pandemic has been much higher than before, and this increase happened in a short period, demonstrating increasing attention to research on plastic pollution worldwide promoted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Another relevant case is Contact From the Future, a digital game on plastic pollution for children created by Panagiotopoulou et al. [125], which proposed to construct awareness and motivate pro-environmental behaviors.

As stated before by some authors [68], in the literature, consumer awareness of plastic is, in general, intrinsically linked to the consumers’ environmental awareness. The results from this work show that consumer awareness of plastic is broader, not limited to environmental consciousness, and each knowledge area has its concerns. These results align with Rhein and Schmid [68], which depicted that “the term awareness cannot automatically be equated with environmental concerns”.

Based on the analysis of the authors’ keywords, the environmental area is prone to concerns; engineering is focused on the solutions, and materials science in the materials that compose the plastic and the development of alternative materials. All of them are intrinsically connected in an attempt to mitigate the pollution caused by plastic. In other words, consumer awareness of plastic is a much broader issue, not just an environmental concern. Even knowing the importance of all the areas analyzed in the search for the growth of consumer awareness of plastic, it is perceived that the literature is not aligned with consumer awareness in their daily life. Literature needs, in addition to focusing on addressing deficiencies described above, meet the real requests of the population in the search for awareness and behavior change for the well-being of society. A schema is shown in Fig. 7.

So, after all, how to raise consumer awareness of plastic? The literature has provided an outstanding contribution to this.

Integrated plastic waste management is a very complex issue and requires engagement at all levels, including producer, consumer, and government. The government is mainly responsible for establishing laws aimed at the common good and supervision so that they are fulfilled. As an example of Law Nº 12,305 in Brazil [126], laws addressing waste management highlight the shared responsibility in which consumers have an essential role.

Public policies are relevant, mainly in cases of consumers who, even knowing their role in the circular economy, do nothing for laziness, selfishness, or lack of awareness. They must change consumer habits through impositions when they do not collaborate. Some consumers contribute from a stimulus, a “currency of exchange,” collaborating only from some advantage. In this sense, it is up to the industries responsible for the reverse logistics of their products to encourage consumers in some way that seems feasible for them to contribute to reverse logistics and the circular economy.

Some authors [127] compared the result of focus group sessions in India with literature about sustainable packages for Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG). Higher environmental awareness was observed in groups with higher levels of schooling. Young generations, especially those still attending school, have shown more awareness and concern about making sustainable choices, while older generations have shown a significant lack of awareness. Conversely, price is one of the most significant factors deterring purchase. Also, a lack of knowledge about the benefits offered by sustainable products makes consumers indifferent toward them.

Similar behavior was observed by Molloy et al. [128], which examined the perception of legislative actions on single-use plastics through surveys and interviews in four Atlantic provinces of Canada. Young generations, students, and high-level school people support the plastic ban. A higher percentage of females support the plastic ban. Men have less probability of contributing to environmentally friendly activities, such as carrying reusable bags.

In Islamabad Capital Territory of Pakistan [129], people who support the plastic bag ban are those with a high education level, health, and environmental awareness. According to the authors, to increase the effectiveness of Islamabad’s plastic bag ban, increasing public understanding of the effects of plastic pollution needs to receive more focus by investing money in awareness programs and campaigns, education investment, and proper implementation machinery.

In Ecuador [130], reusable bags are more likely to be used by the head of household with a high-education level and the rural population. On the other hand, the probability of using these bags reduces when the head of household participates in social organizations.

In Turkey, the use of free-of-charge plastic bags was banned. After this, some authors observed that, among the Istanbul population, women, married people, and high-income groups are more prone to consume plastic bags [131]. These groups should be considered the focal point when designing policies. Based on the authors, “policymakers and environmental organizations should provide the necessary campaigns and training to reignite the tendency to reduce plastic bag consumption as part of environmental awareness.”

There are also cases where the consumer does not contribute to the circular economy due to a lack of knowledge. For example, the survey results found that university students are unaware of the consequences of beverage packaging material choices on environmental sustainability [132]. They do not know how to contribute effectively in their day-by-day activities to the sustainability goal.

More environmentally conscious people are more prone to join environmental initiatives [128, 129, 133]. “Information is one of the most widely used means to promote pro-environmental behavior change” [134] and, consequently, make consumers aware of plastic and its impacts. So, education is an effective way to raise consumer awareness of plastic.

The Internet can improve consumers’ pro-environmental behavior [135]. The Internet has the leading role in providing environmental information, making environmental knowledge popular, and enhancing energy use and social relationships [135]. Moreover, communication through mass media as TV channels open to the public is essential means of information about plastic pollution. Additionally, shocking images, messages of victims of plastic waste, and emotive images are effective in developing consumer awareness since they attract the consumers’ attention and produce a debate on plastic use [136, 137]. “The media has a critical role in educating the public and policymakers on the current environmental concerns regarding plastic pollution” [22].

Last but not least, the plastic importance must be clear to everyone, no matter the way.

It is common in different areas of knowledge to have distinct interests. In an interdisciplinary area such as consumer awareness of plastic consumption and its paramount importance to society, it would be ideal for interests to converge for the well-being of society.

It was possible to observe that each area (environmental science, engineering, and materials science) presents different strategies to reduce the negative impact of plastic on human health and the environment. Each area contributes on its area in developing consumer awareness of plastic:

Concerning the analysis of the authors’ keywords:

So, the authors’ keywords analysis can describe the current scenario of consumer awareness of plastic literature and depict the main concerns of the authors. The analysis can also help outline the future of the research area based on filling in identified deficiencies.

However, all these concerns are not aligned with the ones of the consumer’s habit. It is a severe gap in which literature needs to turn, reducing the “distance” between consumer awareness and behavior.

F. D. B. de Sousa wrote and proofread the manuscript for language editing.

This article does not include human participants or biological material data.

The author declares no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

de Sousa, F.D.B. Consumer Awareness of Plastic: an Overview of Different Research Areas. Circ.Econ.Sust. 3, 2083–2107 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-023-00263-4

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Copy to clipboard

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative